The Newgate Prison Execution Journal: Chilling, Unique, Unpublished

- Peter Berthoud

- Aug 1, 2012

- 7 min read

Updated: Sep 3, 2022

This is the handwritten Newgate Prison execution journal of the "Ordinary", or Chaplain, of Newgate, the Rev. Horace Salusbury Cotton.

Cotton kept his macabre log throughout his tenure at Newgate, even though he was strictly forbidden from doing so.

Between 1814 and 1839 he noted not only the names and crimes of those being executed along with the date of their execution but also his personal observations on any execution that he found particularly interesting.

His journal also contains three very unusual prints including one unique new view of him at work within the prison.

Cotton died in 1846 and his library was sold off by Sotheby's in 1848. For the next century and a half this remarkable journal has barely seen the light of day and has unbelievably, never been thoroughly recorded, photographed or transcribed.

Until now only four small images of it existed in the public realm and they were to be found in the Rare Books catalogue of Peter Harrington, in Fulham Road.

Peter Harrington are currently selling the book, the asking price is £5,000. But before the book is sold, possibly back into obscurity, they have very kindly allowed me to publish here the largest ever selection of high quality images from this very evocative and historically significant little volume.

The title page, in Cotton's hand, reads:

"Convicts executed

since The Year 1812

(inclusive)

at Newgate

H Cotton Ordinary.

appointed 29th July 1814"

On August 22nd 1814 Cotton attended at his first execution, that of John Field, alias Wyld who had been convicted of murder. He notes on the left-hand page that this was "Mr Cotton's first attendance". Cotton had been recording executions for two years prior to him becoming The Ordinary at Newgate, so this must have been a very special day for him.

The same format is adopted throughout most of the 120 pages. Names, dates and crimes on the right, Cotton's comments on the left.

Against the name of John Ashton, convicted of Highway robbery ", he writes "The man sprung up on the scaffold after he was turned off and distinctly cried out 'Am I not Lord Wellington!' he was pushed off again by the Executioner."

In the cases of Mitchell & Hollings he notes that "each man murdered his Sweetheart".

On December 15th the only comments he makes against prisoner Padan's record were that he was hanged "at Execution Dock" and that he was "A Black Man".

Three other typical records from 1832:

"Cook alias Ross was an Irishwoman about 40 years of age, could read but not write. She murdered an old woman of 84 & the principal witness against her was her own son, a Boy 12 years old, she denied her guilt to the last."

"Barrett was born in London - was about 24 yrs of age - could read and write very well - had been a gentleman's servant & for the last 2 years a postman - he had purloined letters at different times containing Bills {??] to the amount of 6000 - was married and had one child."

"Druitt was born in London - bout 30 years of age - could read and write - there were several indictments against him - he was married & left two children.

All of Cotton's record taking was expressly forbidden by the prison authorities. Towards the end of the book Cotton has added a note that explains how in 1836 he had been asked by the new Sheriffs whether he "kept any other Journal relating to Newgate other than the one in the Keeper's Office" and had been forced to surrender "two books" to the Inspectors, who expressed their "regret that any Books [should exist] the entries in which have been kept secret from the Court of Aldermen." They feared that this would allow for reports to circulate that "it would render it impossible to correct if wrong, or contradict if untrue."

"Evidently Cotton did not surrender the present volume, and in a blatant gesture of defiance, adds several signed records directly after his transcription of this injunction!"

From Peter Harrington's catalogue.

Cotton officiated at some very high profile executions, including those of the Cato Street conspirators in 1820, the last case of hanging and beheading in the England,

"They were decapitated after being hung - and buried in the prison in their cloathes [sic.] - Davidson was a black man."

But in the main he attended to highwaymen, burglars, horse thieves, rapists, burglars and those convicted on "unnatural crimes" e.g. "sodomy" or just plain, legal, gay sex as we would refer to it today .

Sometimes a whole list of executions are recorded with barely any accompanying notes. On this page just two captured Cotton's attention:

Edward Harris: "This case made a great noise at the time, he so persisted in his innocence, that some even believed it - he was known by the name of Kiddy Harris."

William Probert: "Probert who was connected to a convicted murderer and Cotton notes that this "probably sealed his fate. He appeared to die in horrible despair."

Cotton includes three images of himself at work inside Newgate. All three may be physically accurate but all flatter Cotton by portraying him as the spiritual guardian of those to whom he ministered, rather than the cruel bully that he actually he was.

This first little print is based on a water-colour held by The Tate "Dr. Cotton, Ordinary of Newgate, announcing the Death Warrant," which is inscribed, "Sketched on the spot by a prisoner W. Thomson Sepr 1826"

This second print is based on "'The Upper Condemned Cell at Newgate Prison on the Morning of the Execution of Henry Fauntleroy" at the Museum of London. But the third and final print is a complete mystery.

Peter Harrington say that all three Thomson "etchings appear to be entirely unrecorded, and we have been able to trace only one other example of Thomson's work." Quite how that got produced inside a prison, as Cotton purports is also a mystery.

This last print shows Cotton looking much as he was described by Bleackley in his Hangmen of England "a robust, rosy, well-fed, unctuous individual".

But Bleackley went on to add that Cotton's "condemned sermons were more terrific than any of his predecessors, and he was censured by the authorities for 'harrowing the prisoner's feelings unnecessarily'".

Charles Dickens visited Newgate during Cotton's time as Ordinary and agreed with Bleakley that Cotton's sermons and his cruel management of the prisoner's final services was barbaric.

Dickens, writing in 1836, described the scene in the chapel. At that time the prison Chapel also housed a special pew for prisoners condemned to death.

THE CONDEMNED PEW; a huge black pen, in which the wretched people, who are singled out for death, are placed on the Sunday preceding their execution, in sight of all their fellow-prisoners… to hear prayers for their own souls, to join in the responses of their own burial service, and to listen to an address, warning their recent companions to take example by their fate, and urging themselves, while there is yet time – nearly four-and-twenty hours – to ‘turn, and flee from the wrath to come!’

Imagine what have been the feelings of the men whom that fearful pew has enclosed, and of whom, between the gallows and the knife, no mortal remnant may now remain! Think of the hopeless clinging to life to the last, and the wild despair, far exceeding in anguish the felon's death itself, by which they have heard the certainty of their speedy transmission to another world, with all their crimes upon their heads, rung into their ears by the officiating clergyman!

At one time – and at no distant period either – the coffins of the men about to be executed, were placed in that pew, upon the seat by their side, during the whole service. It may seem incredible, but it is true. Let us hope that the increased spirit of civilisation and humanity which abolished this frightful and degrading custom, may extend itself to other usages equally barbarous; usages which have not even the plea of utility in their defence, as every year’s experience has shown them to be more and more inefficacious.

You can read Dickens’ full account here and see an image of the condemned pew in use ( before Cotton took office) here.

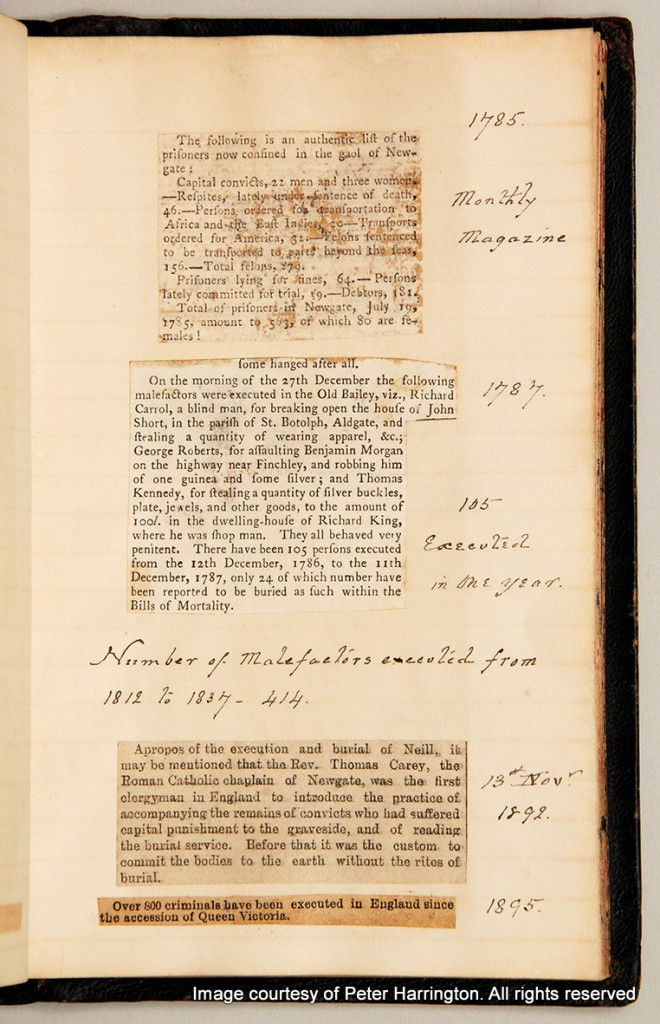

Towards the rear of Cotton's notebook are several pages of cuttings, on Newgate in particular, and executions in general. The span of dates is immense, they begin in the mid 18th century and continue almost to the 20th. It seems likely that Cotton began the collection and that it was later added to by surviving family members.

Obviously these cuttings are not as rare or unique as the main body of the book but they still make fascinating reading.

There must surely be an individual or institution who would be willing and able to properly document the contents of Cotton's unique record of Newgate's executions and put the results into the public domain.

I am not a professional historian, I know that I have merely scratched the surface in this account. I do hope that in raising awareness of this rare document I might help, in some small way, to promote its general accessibility in future.

I am indebted to Peter Harrington for giving me the opportunity of seeing this incredible book in person and reproducing these images from it. The images are by Ruth, thank you so much and special thanks to Glenn, his most erudite and comprehensive catalogue entry made this post so much easier to write. There are many other entries from the book in Glenn's account that I didn't have space for here.

I'll be returning to this blog to feature more incredible London treasures from Peter Harrington soon.

In the meantime if you or your institution might be able to help ensure that the contents of this unique book become publicly available please do contact Peter Harrington direct.

If you just want to buy it and lock it in a bank vault - please don't!

Peter Harrington 100 Fulham Road Chelsea, London, SW3 6HS

The Shop is Open: Mon-Sat, 10am-6pm

Peter Harrington also posted about the episode.